I once decided not to take any photographs at all on a trip through the south of France. I resolved instead to collect written “snapshots” in my journal—jotting down every intriguing thing that caught my eye. I frequently pulled over to the side of the road to take notes: “kids emerging from woods with berry baskets slung on their arms;” “field of lavender pulsing neon-bright in the sun.”

I’m reminded of that experiment when I find myself returning to the same region. This time I wonder whether it is possible to collect olfactory “snapshots” in a similar way—the scent of orange blossoms spilling over the top of a walled garden; the briny zephyrs blowing in from the Mediterranean; the delicious aromas of roasted peppers, basil, and garlic emerging from a bustling café; the dreamy rapture of pressing my face into an overblown rose.

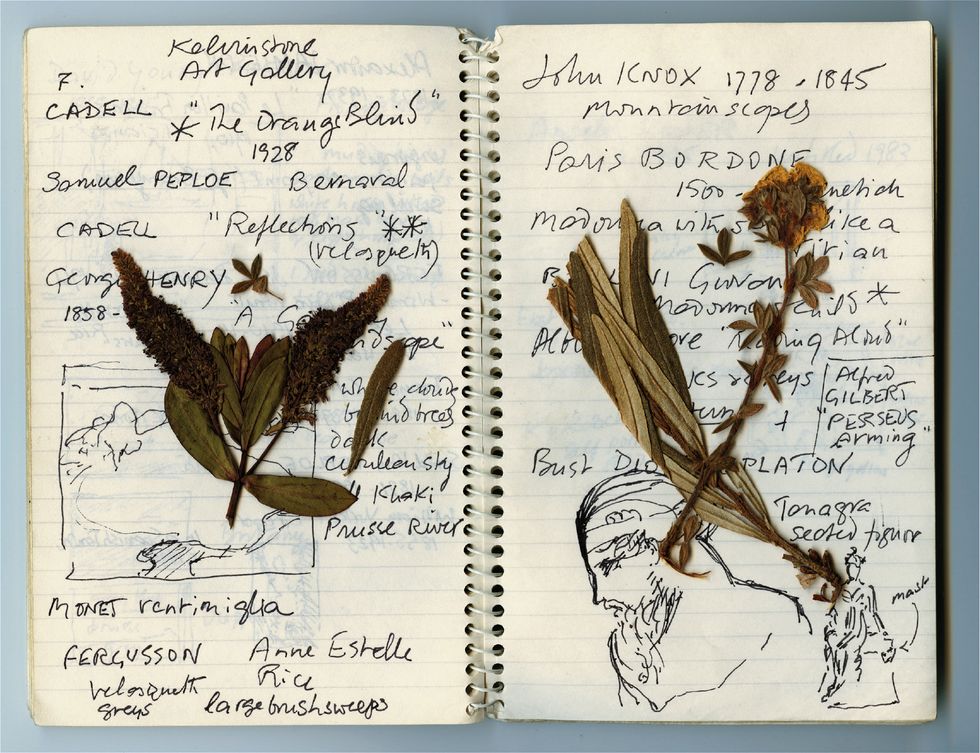

An artist and herbalist, Diptyque co-founder Desmond Knox-Leet filled journals with notes, sketches, and even wildflowers during his travels.Courtesy of Diptyque

I am in France to study scent, how the notes of a flower, fruit, spice, wood, or herb mingle and play against each other, how they are coaxed out of their source materials and transformed into something tangible, such as a candle, perfume, or soap. My teachers are masters of their craft: the perfumers of Diptyque, the iconic French fragrance company that began as a chic little curiosity shop in 1961 on Paris’s boulevard Saint-Germain.

Two years in, the three artist friends who founded it had the idea to create colored candles, but the candlemakers they contacted suggested scented candles instead. They found their niche: blending aesthetics and fragrance. Before long the trio was developing their own scents, olfactory “souvenirs” of places they’d been—many based on their personal histories.

Painter and calligrapher Desmond Knox-Leet, for instance, was a code-breaker during World War II who’d grown up in a French Riviera house scented with potpourris and pomanders. Christiane Montadre-Gautrot, a graphic and interior designer, spent her holidays as a child on the apple-orchard-filled Normandy coast, while thespian and set designer Yves Coueslant had been raised in Vietnam, enveloped in the scents of tuberose, citrus, and exotic spices. Their experiments with perfumes played out like fragrant memoirs.

The town of Grasse, France.GETTY IMAGES/ISTOCKPHOTO.

While their journey began in Paris, my trip starts in Grasse, a village founded some 900 years ago on the slope of a natural mountain amphitheater overlooking the Mediterranean. Grasse earned its reputation as The Perfume Capital of the World, in part, through luck of topography—its surrounding hills and alpine valleys create numerous microclimates; fed by mountain springs they support a proliferation of native flowers. With each passing generation, local perfumers expertise has deepened and grown.

Grasse is livelier and grittier than a delectable picture-postcard village like Saint-Paul de Vence or a died-and-gone-to-heaven paradise like Cassis’s Les Roches Blanches. But I like its contrasts—how I can turn off a street abuzz with commerce and cars and suddenly find myself on a dim, zigzagging medieval lane barely wide enough to push a wheelbarrow along, then climb a steep passageway, musty as a damp cave, to a terrace where the view suddenly pops open to reveal the sea 12 miles away and nearly 1,200 feet below.

Grasse is also home to The International Perfume Museum, where I learn, for example, that every culture around the globe, from the Aztecs to the ancient Egyptians, developed fragrances independently, usually in the form of incense offered to gods. I also discover that humans have gone to great (and expensive!) lengths to draw out scents from their sources, starting with giant presses that would squeeze out fragrant oils.

These have evolved into a multitude of complex techniques such as “supercritical fluid extraction,” which involves inundating a vat of organic material like jasmine petals with highly pressurized carbon dioxide to dissolve, extract, and then collect its myriad fragrance molecules.

At a villa perched on a promontory above Grasse, I meet Fabrice Pellegrin, a world-renowned expert in the art and chemistry of fragrances. The son of a perfumer and grand-son of a jasmine-picking grandmother, he has created perfumes for many couture houses, including Diptyque.

He says early in his career “I put a lot of ingredients into my formulas. Now I have become more focused and precise. I want the raw materials to echo each other. The challenge is for each fragrance to be simple, direct, expressive, and balanced.”

Sunny yellow mimosas, which inspired a Diptyque candle of the same name, bloom every February on the hills of Tanneron along Provence’s Route du Mimosa.Courtesy of Diptyque

It’s a heady task. It turns out that combining scents with wax is far more complex than, say, baking a cake, because of the unpredictable interactions of ingredients. Imagine if sugar lost sweetness when mixed with one kind of flour, gained it with another, and turned bitter in an oven even 10 degrees too hot. Now imagine equally capricious behavior from every other ingredient in the batter. No wonder budget candles use synthetic components.

Diptyque uses natural fragrances and a repertoire of waxes in different proportions to ensure each fragrance formula behaves as expected when the candle is lit, as well as when it’s cold. At the factory workers belabor each step, warming the jar before adding the melted wax so it won’t crystallize; topping off after the wax is cooled; straightening the wick three times during the process; smoothing the surface with an infrared heater; and finishing each candle by hand. It’s craft and chemistry and imprints of florals and spices, herbs and woods from near and far.

Villa Noailles, a 1920s art center in Hyères known for hosting visionaries like Giacometti and Man Ray, often partners with Diptyque.RALF SCHERNEWSKI

On my last day in France, I arrive at Villa Noailles, a strikingly modernist house overlooking the town of Hyères. Built in 1923, the villa now hosts art exhibitions, but it’s the “Cubist ocean liner” architecture (as a guest once dubbed it) that has me bug-eyed with delight.

For decades the house’s bohemian owners hosted artists’ residencies, inviting the likes of Giacometti, Mondrian, and ManRay to live, work, and collaborate there. The friends who started Diptyque have passed away, but their very first scented candles are still in production 60 years after they debuted in the shop—Thé (Tea), Cannelle (Cinnamon), and Aubépine (Hawthorn).

Meanwhile, the company honors the proverbial spark of their creative spirits by cultivating partnerships with places like Villa Noailles—which often carries Diptyque candles with exclusive scents in its retail shop—and small makers like a ceramics factory turning out new pottery cups for a collection of oversize candles.

With up to five wicks and a weight of nearly 3 1/2 pounds apiece, the new larger candles won’t fit easily into my luggage. But before I leave Villa Noailles, I slip away onto one of the villa’s chalk white terraces to collect a more personal—yet equally potent—souvenir. As a warm breeze washes down off the mountains,I close my eyes and take in its soft, mingled aromas of rosemary, eucalyptus, and lilac before they drift out to sea.

Source: Veranda